Approximately 100 years ago, a colonial conflict of great breadth began on the south side of the Mediterranean. Initially seen as an “indigenous” rebellion, the conflict evolved into an intense war, the final phase of which involved the intervention of two great colonial powers (France and Spain). Looking at the Rif War (1920–1926) in a region of what is now Morocco, then claimed by Spain, as an example, this article presents a critical analysis of a conflict rich in lessons for current humanitarian challenges and the sometimes-difficult relationship between humanitarian actors and the parties to a conflict. Assessed in the light of its human cost, which is largely forgotten today, the Rif War can feed debates through necessary historical reflection surrounding humanitarian action and the role of the International Committee of the Red Cross. It will also examine the complicated connections between historical truth, collective memory and the political difficulties inherent to reconciliation.

* The author wishes to thank Fabrizio Bensi at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) archives and Karim Bouarar for his knowledge of the Rif region.

History is a bunch of lies that people have decided to agree upon.1

Napoléon Bonaparte

In Julien Duvivier's famous 1935 film, La Bandera, a platoon of Spanish legionnaires finds itself isolated on a rocky outcrop, under fire from rebel Moroccan tribes (see Figures 1 and 2). In the final scene, the group's only survivor stands to attention among his fallen comrades and salutes the forces sent to relieve them.2 The scene depicted in the film is only just over a century old, but how many people know about the war in which it was set? The year 1921 marked the start of a conflict that is now largely forgotten, although it remains one of the most important colonial wars of the twentieth century. Certain specialists regard it as a crucial landmark of Arab nationalism. However, any anniversary of the Rif War3 is very unlikely to be ever celebrated because it was in no way a “fresh and merry war” (as Kaiser Wilhelm II expected the First World War to be4 ). This article aims at reviewing this long-forgotten conflict from a contemporary point of view, especially in comparison with so-called new phenomenology of conflicts and their humanitarian consequences. This article will first examine the political and military developments of the Rif insurrection in the post-First World War context. It proposes looking at the diplomatic negotiation attempts initiated by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; in French, CICR) in order to secure an agreement from Spain and France to deploy aid activities in a situation of civil war. It will then describe the consequences of the legal vacuum and some aspects and characteristics of the Rif Conflict. The arguments put forward by the ICRC and the States involved to deny and block humanitarian intervention will later be reviewed. The article will finally explore the lessons that can be drawn today from a 100-year-old conflict and propose some hypotheses on how this conflict has largely escaped humanitarian history.

Figure 1. Abd el-Krim rejecting the Spanish, in 1921, Battle of Annual, during the Rif War, National Overseas Archives.

Figure 2. Film poster. Source: Le blog du cinéma.

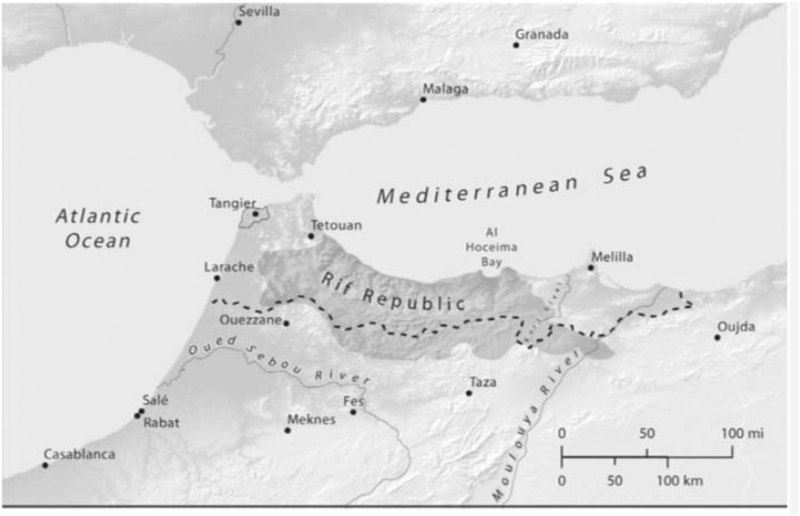

The Rif, a region in the northern part of what is now Morocco (see Figure 3), is mountainous, relatively dry and very difficult to access. Located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Ouergha River to the south, the Rif is bordered on the east by the Moulouya River and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. It is mainly inhabited by Imazighen (or Berber) communities, who are Sunni Muslims. In 1905, France and Spain had the most influence over the sultanate of Morocco, but it was still coveted by Germany, a latecomer with its “Drang nach Afrika” (push into Africa), which was claiming the Tangiers region. In 1911, Berlin sent a gunboat to the Bay of Agadir,5 under the usual pretext of claiming that its nationals were under threat. This show of strength created serious tensions in Europe, and Germany was subsequently offered additional territories in Equatorial Africa and Congo in exchange for giving up its claims on Morocco. In 1912, the Treaty of Fez6 between France and the Sultan of Morocco formally created the French protectorate in Morocco, but gave Spain some sovereignty in the north, established by a separate treaty between France and Spain. This 1912 treaty established a French zone to the south of the Rif (known as “Maroc utile”), a Spanish zone to the north with Tetouan as the capital, the Tangier International Zone and a Saharan territory to the south of the French zone, also attributed to the Spanish. The Treaty of Versailles (1919)7 confirmed that Morocco would remain under French and Spanish protection, thus definitively ending any German claims to the country.

Figure 3. Map of the Rif Republic.

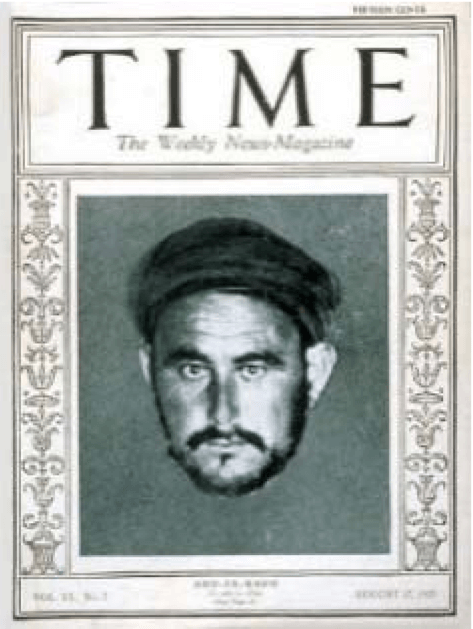

In 1912, the Spanish protectorate in Morocco consisted of some small cities along the Atlantic Coast, Asilah, Larache (el-Araich (1911)) and Ksar el-Kebir, as well as a narrow strip on both sides of the Ceuta–Tetouan road.8 The two enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla had been attached to Spain since the sixteenth century and served in 1912 as bridge heads for the Spanish penetration. Spain, which had lost Cuba and the Philippines in 1898, dreamed of gaining new possessions providing territorial continuity9 with the Iberian Peninsula and of realizing ambitious colonial plans beyond the narrow coastal strip of land that it already controlled. Morocco was the perfect target for new expansion in North Africa. It was not until 1920 that Spain's expansion effort resulted in military activity, particularly in the Chefchaouen region. The aim was to control territories occupied by Berber tribes resisting mineral exploration and Spanish colonization in general. For that operation, Spain had created the Tercio de Marruecos in 1920, better known as the Spanish Legion,10 which was later placed under the leadership of Commander Francisco Franco.11 Although the Spanish army scored a number of fairly easy victories at the start, its progress in the Rif prompted the gradual mobilization of Berber tribes, which submitted to and gradually rallied to the authority of Emir Abd el-Krim al-Khattabi, a well-known Rif native and chief of the Aith Waryaghal tribe (see Figure 4). Abd el-Krim was an Islamic judge, journalist and teacher. He initially believed that Spain would modernize the protectorate and that he could play a role. He gradually realized that colonization had objectives other than developing the country. He then turned against Madrid and headed the uprising. Abd el-Krim was a local tribal chief, but he identified with the wider anti-colonial struggle, such as that of Emir Abdelkader in Algeria. Indeed, a small number of his troops were Algerian deserters from the French Legion, some of them probably inspired by Abdelkader's revolt. Interpretations differ as to his political objectives, but all historians agree that he wanted broad autonomy for his people, although he remained unclear about the concept of independence and how modern a State he wanted to create.

Figure 4. Cover of Time magazine, 17 August 1925.

After a series of initial military successes that created great optimism among the Spanish generals, the Battle of Annual in Temsamane in July 1921 resulted in a crushing defeat for the Spanish, who lost an estimated 10,000–16,000 men. The military dictatorship installed after the Annual defeat immediately decided to send huge numbers of reinforcements (36,000 troops) and heavy equipment, but that yielded little success on the ground. Although the Rif tribes had fewer numbers and were disorganized, the terrain gave them a decisive advantage and they were very mobile, successfully repelling the forces engaged by Madrid. In these confrontations, some Spanish battalions suffered up to 75% losses.

Buoyed by his military success, Abd el-Krim announced the creation of the Rif Republic in September 1921 and introduced sharia law in the territories he controlled. However, he remained loyal to the Sultan of Morocco. According to sources available,12 it is quite established that Abd el-Krim had plans to create an advanced and sovereign State, most probably vaguely inspired by the Kemalist experience,13 but also influenced by Islamist reformist ideology (Rashīd Riḍā14 ). Some authors strongly dispute the modern nature of the Rif State and prefer to describe Abd el-Krim's project as an islamo (Din)–nationalist (Watan) State detached from tribal structures.15 It is relatively clear that the transformative ambitions of Abd el-Krim had to take into account the limited reform capacities of a very conservative population.

Abd el-Krim was not a mystical prophet waging jihad and wanting nothing to do with heretics, in the mould of Muhammed Ahmed ibn-Abdullah (otherwise known as “al-Mahdi”) in Sudan in 1880. Neither was he a pure Berber rogui16 competing for power. Although he was above all regarded as a local hero, he nevertheless sought to strengthen his international position by sending envoys to some European capitals, generally members of his close family, or by sending letters through foreign journalists and collaborators.17 He was considered as an example in the Muslim world. The Rif Republic was largely a proto-State based on the tribal system and a fairly strict form of Islam called Salafism that stands in opposition to maraboutism and tribalism. Abd el-Krim still sought to develop modern institutions; he centralized his administration and collected taxes vaguely based on the Kemalist model,18 thus showing that he had not cut all ties with European civilization. His diplomatic efforts were directed towards European civil society and its political elites, and he did not really seek to establish any pan-Arab or pan-Islamic solidarity.19

The Rif State project took the form of an embryonic administration only because the rest of the programme met a stiff resistance from its own people very much attached to the tribal structure and opposed to any kind of secularism. The Rif Republic was not recognized by any State despite efforts to attract the sympathy of the League of Nations (LN).20 France and the Sultan of Morocco, for different reasons, did their utmost to sabotage any form of political or symbolic recognition of the Rif State, amongst them, the attempts to attribute Caliphate to Abd el-Krim.21 At the same time, Abd el-Krim tried to “internationalize” the conflict by mobilizing Muslim and anti-colonial forces abroad and by asking for humanitarian support, but with limited success. He did not create any relief organization, which might have convinced the ICRC to do more. With hindsight, and with the usual caveats, it would probably have been fairly possible for the ICRC to establish dialogue with Abd el-Krim at least through intermediaries and to take action.

In the following years, the war became a disaster for Madrid. The Spanish retreated on all fronts. Their military positions were taken one by one, although coastal towns like Tetouan, Larache (El-Araich), Ksar el-Kebir, Zeluan and Asilah remained in Spanish hands or were rapidly retaken after a few months of occupation. The French were not unhappy to see the Spanish being defeated. The Spanish retreat in 1924 encouraged Abd el-Krim to open a second front, this time in the south, and he launched raids on French military positions.

In April 1925, the Rif troops started to carry out large-scale military operations in the south against the French-controlled part of Morocco, tipping the country into conflict. Fez was threatened and the French protectorate as a whole was now in a precarious situation. Talks between Abd el-Krim and French envoys were inconclusive. France mobilized and deployed 160,000 men from its regular army that could be supplemented by colonial troops, mostly from North Africa and Senegal, along with sixteen air force squadrons.

The two colonial powers quickly reached a cooperation agreement to carry out joint military action. France's Resident-General in Morocco, Marshal Lyautey, was deemed too cautious, too political and, above all, too close to the Moroccans, and was quickly replaced by a new official transferred from Algeria, Theodore Steeg. However, the real architect of the military campaign was Marshal Philippe Pétain who, in his own words, “did strategy not politics”. His aim was no longer to teach Abd el-Krim a lesson, but to crush the revolt once and for all.

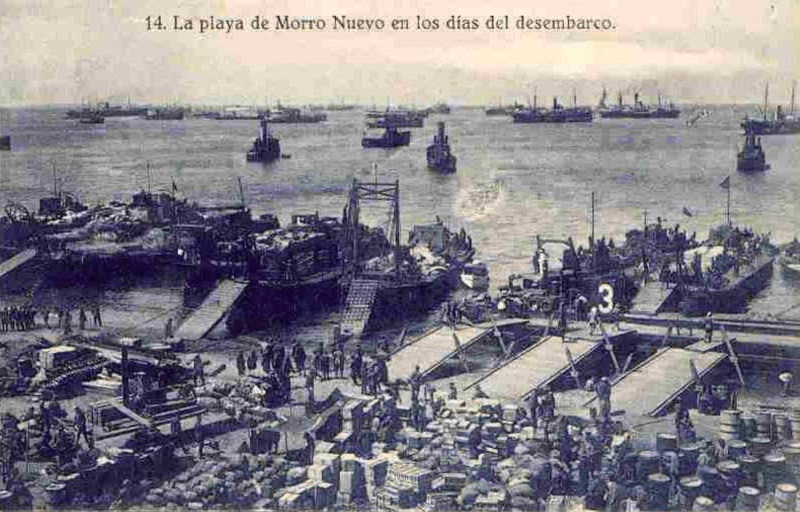

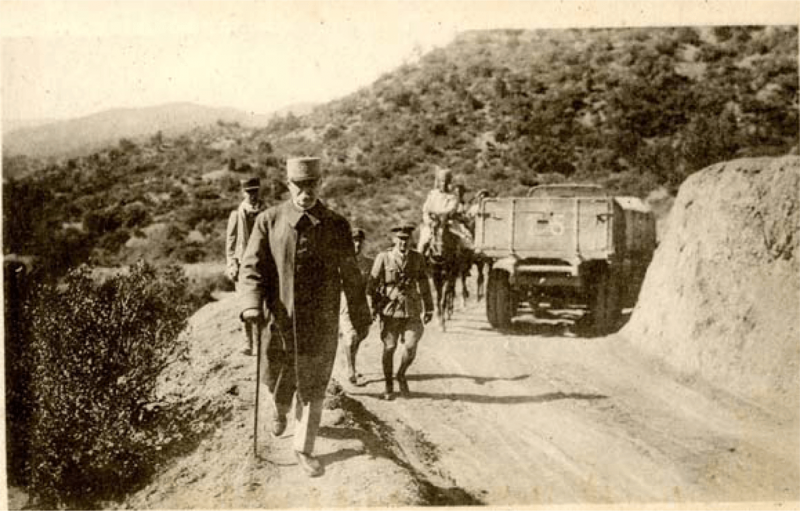

On 6 and 7 September 1925, an armada of more than 100 Spanish and French ships unloaded 16,000 men and heavy equipment in Al-Hoceima Bay after unleashing some fearsome early artillery fire (see Figure 5). In all, eighty-eight aircrafts bombed the region to allow the troops to disembark. The operation later served as a template for Operation Torch in North Africa in 1943 and the Allies’ Normandy landings in 1944. The operation to take back Morocco had begun. No fewer than 600,000 men (against approximatively 15,000 Riffian combatants) took part in offensives intended to take control of the Riffian territory. Spain and France were supported by equipment provided by the United Kingdom and Germany. During this amphibious landing operation Spanish troops could disembark around 18,000 men and the French army up to 20,000.22 In total, the joint expeditionary corps would reach 120,000 men and 400,000 auxiliary troops (for a picture postcard of General Pétain inspecting the front, see Figure 6).23

Figure 5. Spanish troops landing at Al-Hoceima Bay on 8 September 1925. Source: Pinterest.

Figure 6. General Philippe Pétain inspecting the front. Postcard, Pascal Daudin's private collection.

After a year of intensive military action, the losses were huge, the tribes disbanded and Abd el-Krim had lost his last supporters, including those in his own tribe. In April 1926, Abd el-Krim's envoys met with French envoys in Oujda, telling them he could accept the offers of peace and autonomy made by the Sultan of Morocco, whose sovereignty he did not dispute. However, the talks failed. We know that the discussions faltered after three weeks on the matter of prisoner exchanges, and broke down for good on 6 May 1926. Abd el-Krim again ordered the execution of a group of Spanish prisoners, signalling that he no longer intended to negotiate. The Rif troops were defeated a few months later, although pockets of resistance lasted into 1927.

After surrendering to French forces, Abd el-Krim was first exiled to La Réunion, but escaped to Egypt in 1947 en route for France. He never returned to Morocco.

The Rif War took place in a kind of a legal vacuum. In the 1920s, non-sovereign actors were deliberately excluded from international law. At that time the laws of war only applied to conflicts between sovereign States,24 such as the Hague Convention of 1907. Although the status of the colonies or protectorates was legally uncertain, the French and Spanish authorities took the view that the Rif Conflict was taking place within a sovereign State. As a result, the Conventions did not apply to such a situation. It was not until 1949 and 1977 that the Geneva Conventions included the notions of internal armed conflict and national liberation wars. At the time of the Rif War, thinking of internal conflicts as part of the system of international law was not far beyond the horizon,25 but totally segregated from the colonial space. According to some historical sources, the ICRC was rather frustrated by the situation and, in particular, to be denied access to detainees.

In addition, after the First World War, the States were more focused on avoiding further military conflagration than developing jus in bello instruments.26 The idea of regulating civil war truly emerged only after the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), but the main resistance against such a concept (which was later formalized as Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions) prevailed until 1949 and was mainly led by colonial powers which ruled millions.27 Colonial powers like France and the United Kingdom wanted to deal with any sort of rebellion according to their own terms until they had to rally the majority and decided to shape the law. Today, the applicability of the doctrine of belligerency28 still remains in the hands of States29 and still orients all negotiations regarding humanitarian access to zones controlled by non-State actors.

As for the ICRC, in 1920–1921, it did not have an explicit mandate to take action in situations of civil war (what international humanitarian law refers to today as internal armed conflict). However, it is interesting to note that at the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross in 1921, the problem of internal conflicts and the ICRC's role was explicitly addressed by the International Red Cross Movement.30 At that conference, Resolution XIV31 stated that:

The Red Cross, which stands apart from all political and social distinctions, and from differences of creed, race, class or nation, affirms its right and duty of affording relief in case of civil war and social and revolutionary disturbances.

However, ICRC action depended on a National Society making a formal request: only then could the ICRC approach the government concerned. If the government refused, the ICRC was nevertheless authorized to voice its concern publicly.32 In 1925, the Swiss Red Cross asked the ICRC to appoint a representative to collect information on Swiss soldiers in the Spanish Legion captured by the Riffian rebellion. That assignment was refused by the Spanish and French authorities33 and firmly discouraged by the ICRC.34

I have always been reluctant to use asphyxiant gases against indigenous people, but after seeing what they did in the Battle of Annual, I will use them with great delight.35

The defeat in the Battle of Annual36 and the Massacre of Monte Arruit,37 in which 2000–3000 soldiers of the Spanish Army were killed after surrendering the Monte Arruit garrison near Al Aaroui, were a terrible blow for the Spanish military establishment. Moreover, the discovery of mass graves in Nador and other cities conquered by the Riffian troops stirred up great emotion in Spain and fomented a desire for a modern-day Reconquista. One notable aspect of the conflict was the use of poison gas38 against the Riffian rebels in spring 1924. In that regard, King Alfonso of Spain explained that “vain humanitarian considerations” needed to be “set aside” in order to use blockades for starvation and intensive gas attack to help with the “extermination of malicious beasts” who were aiding rebellious Moroccan tribes.39 Spain used German and French expertise to develop production plants in Spain and in the enclave of Melilla. Some material was also shipped directly from remaining German stockpiles. The French army also ordered and stored mustard gas shells, although it is not clear where and how they were deployed. The Spanish air force dropped numerous “X” bombs on the theatre of operations.40 Few historians dispute the fact that the Spanish army made heavy use of these weapons, and freely admitted doing so.41 According to some authors42 who had access to Spanish and British military archives, the use of gas was part and parcel of the counter-insurgency strategy against the Rif Rebellion and usually directed against large concentration of civilian dwellings. Some former Spanish pilots, a few being still alive in the 1970s, publicly confessed having dropped bombs filled with poison gas in Morocco.43

In the beginning of the 1920s, the issue of poisonous gas was already subject to several condemnations, which led to their prohibition.44 However, it seems that colonies were considered as exceptions45 or as not being of concern.

Towards the end of 1924, the ICRC had received information from several sources, probably from public sources such as the press,46 that poison gas had been used in military operations, although it is fair to say that it probably did not have the full details of what was happening in Morocco.47 Pressured to act, the ICRC chose to ask the Spanish Red Cross about its government's policy. The Spanish Red Cross responded a few days later that it had received a formal denial from the military authorities concerning such use of poison gas. The ICRC expressed its “relief” in its response to the National Society.48 It is difficult to admit that this reaction was the result of pure credulity and not subdued complacency. Some authors49 argue that Abd el-Krim might have sent letters to the ICRC and to the LN on this matter but we could not recover any trace in official archives of either organization.

In 1918, the ICRC had played a major role in a campaign to ban these types of weapons, which resulted in the adoption of the 192550 Geneva Protocol.51 In its further correspondence with the Spanish government, the ICRC referred to this protocol but said that it had very serious doubts about allegations regarding the use of these weapons. It never mentioned these allegations in its public communications but praised instead the Spanish Red Cross for the excellency of its medical response in the field.52 Surprising as it may seem, military operations in the Rif did not influence the signature of the Geneva Protocol, though Spain did not sign up to the instrument until 1929.53 Unfortunately, this was not the last use of gas in conflict situations.54

The Rif attracted a few foreign fighters, but they were subject to serious discussions between the belligerents. Among them was the so-called Lafayette Escadrille, an American squadron originally created during the First World War to support the French army on the front. In the summer of 1925, a group of sixteen American aviators joined the French contingent.55 The squadron was later renamed the Escadrille de la Garde Chérifienne in order to avoid reaction from the US public opinion largely opposed to colonial politics. The squadron's members were nominally attached to the armed forces of the Moroccan Sultan, the formal ruler of Morocco, even bearing the sultanate's emblem of a five-pointed star on their uniforms. The leader of the American outfit was led by a soldier of fortune, Colonel Charles Sweeny, who proposed his services to the French authorities and recruited a dozen veteran pilots who had fought in the Lafayette Escadrille during the war. The squadron flew more than 400 missions and bombed symbolic cities such as Chefchaouen,56 in some sort of premonition of Guernica.57 The American Legation in Tangier finally warned the American aviators that US law prohibited fighting in a war58 against people with whom the United States had no quarrel.59

In the end, the US government, concerned about violations of neutrality and hostile domestic opinion, brought the chapter of the Escadrille Chérifienne to a close after only six weeks of combat operations.

The Spanish foreign legion counted many Portuguese and a few European citizens in its ranks. However, the harsh discipline enforced by Spanish officers did not attract a large number of foreigners and was conducive to desertions. Abd el-Krim enjoyed the support of a couple of Spanish foreign legion deserters, and some Turkish and European volunteers – mainly Germans60 – who served as “military advisors” for training Riffian harkas.61

In 1925, the Spanish Red Cross had created two research bureaus62 to trace prisoners who had fallen into the hands of Rif rebels. It is difficult to know whether the ICRC was cultivating support by offering its help or was rather using the question of foreign and Spanish combatants as a political back door to obtain a license to operate in the region. In a subsequent meeting between ICRC president Gustave Ador and French ministers Briand and Painlevé in Geneva, the ICRC used the “prisoner argument” to justify and suggest a mission.

Telegram no. 562 O. O. — “When you report losses suffered by dissidents, just state the number of people killed or injured and the number of animals killed, without specifying age or sex.”63

There are few reliable sources regarding the human toll of the Rif War. In military terms alone, some sources suggest that 63,000 Spanish, 18,000 French and 30,000 Riffian troops died during the conflict, although these figures should be treated with caution.64 There is no credible information about civilian deaths and numerous experts believe65 that the numbers of civilians killed or wounded were systematically underestimated or simply not taken into account. However, we know that it was an all-out war, that the various military operations caused heavy civilian casualties and that the civilian population, assets and infrastructures were clearly targeted. Available figures66 are merely extrapolations based on military losses. However, it is clearly established that military operations on both sides affected food production infrastructure, such as livestock, markets, agricultural land, dwellings and harvests.67 In 1923, military planners took the view that the Rif would have to be razed completely in order to crush the rebellion. This left little scope for distinguishing between civilians and combatants. As a result, no quarter was given except for those who surrendered without fighting and agreed to collaborate. It would also be naive to think that the widespread use of poison gas in aerial or land bombing operations only affected the combatants.

In the 2000s, a few Moroccan non-governmental organizations again highlighted the fact that the Riffian people seemed to suffer from abnormally high rates of cancer (of the thyroid) and physical malformations. However, no international and independent scientific studies have been carried out to look into this phenomenon.68

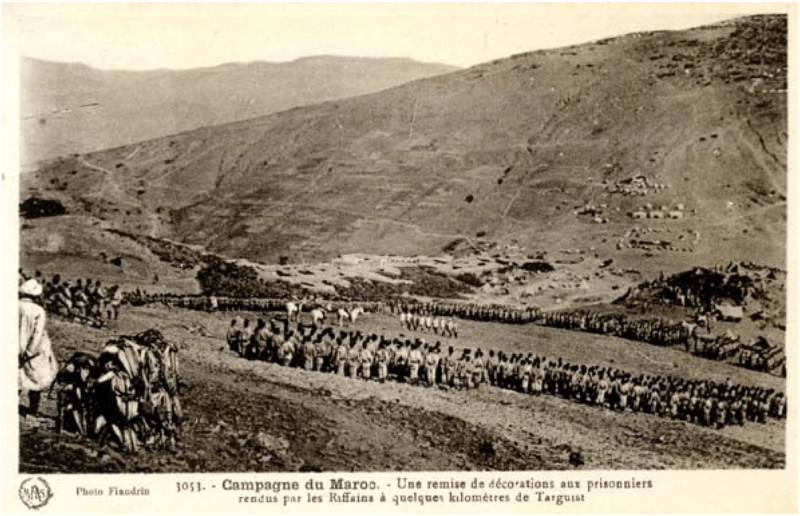

The Riffian combatants also left much to be desired in the way that they conducted hostilities. In general, captured Spanish soldiers could not expect any clemency from Riffian fighters (though sometimes prisoners were returned; see Figure 7). On several occasions – such as the Battle of Annual rout, the defence of Mont Aroui and in Nador – Spanish troops were executed and mutilated, with the death toll estimated between 10,000 and 14,000. These summary executions prompted horror and dread among the Western public. Such massacres naturally fed Spanish patriotic fervour and stoked a compulsive desire for revenge within the army.69 Pictures taken during the 1925 offensive70 show mutilations of captured Moroccans, with severed heads, noses and ears which were collected by Spanish legionaries, paraded as war trophies and worn as necklaces or spiked on bayonets. Atrocities were perpetrated by both sides without much restraint.

Figure 7. Morocco campaign. A presentation of medals to prisoners returned by the Riffians a few kilometres from Targuist. Postcard, Pascal Daudin's private collection.

Beginning in the second phase of the conflict, in northern Europe and the United States, voices arose to call for charitable action. The fate of civilians was often brought up in the press at the time.71

There is little evidence of any large-scale humanitarian action in the Rif region for lack of available means and because of the blockade put in place, first by Spanish troops and later by the French. Civil society and charitable organizations also played a fairly marginal role and committed few resources to the war.

During the hostilities, very few relief actions were attempted, and the rare initiatives that were successful were undertaken by local organizations72 managed by private individuals or very small associations without great resources. These activities were concentrated almost exclusively in the city of Tangier, where several thousands of families had taken refuge. Some volunteers to the Riffian cause offered their services in combat zones, but these gestures are anecdotal from a historical point of view.

The Spanish Red Cross saw a significant increase in its health-care capacity during the conflict, but the hospitals established were entirely dedicated to Spanish troops and to civilian victims of Riffian attacks. In December 1921, after Spain's defeat in the Battle of Annual, a representative of the Spanish Red Cross was asked by Madrid to negotiate a prisoner exchange, which failed because hostilities then resumed. Spanish prisoners were repatriated in 1923 in return for a substantial ransom, but of 550 prisoners only 326 made it home, the rest dying of hunger or being executed.73 Although it is difficult to attribute all of these events to the orders of Abd el-Krim himself, he did not prevent the numerous abuses perpetrated by the harkas, which exacerbated the conflict. On the ground, the Riffian troops were highly independent and carried out razzia (raids) without strong coordination.

Generally speaking, the Spanish74 and French Red Cross societies were in agreement with the positions of their respective governments and sometimes participated in efforts to hinder the ICRC's timid initiatives.75

The ICRC was often satisfied to simply communicate questions or demands from National Societies concerned by the situation in Morocco (for example the Turkish Red Crescent) to the relevant Red Cross society without really taking action, even sometimes discouraging action, as was the case with the Swiss Red Cross.

At the international level, several organizations like the Society of Friends (Quakers),76 the North Africa Mission Hope House Hospital, Save the Children Fund77 and the Near and Middle-East Association rolled out concrete programmes for affected populations.78

A solidarity movement was also created in the Muslim world, at the heart of which the British Red Crescent79 played a central role and received contributions from some National Societies (such as the Egyptian Red Crescent). It nevertheless played only a modest role limited to the transfer of funds for material assistance to refugees in Tangier and for locally recruiting doctors, some of which were sent to zones held by the Riffian insurrection.

In 1922, via its representatives in India and in London, the British Red Crescent officially requested permission from the British authorities to send a contingent of Muslim doctors to Morocco. This initiative was strongly discouraged by the British ambassador in Madrid, Esme Howard, who declared that such an act would gravely undermine the image of the United Kingdom in Spain, so much so that the British government rejected the request to visit Spanish prisoners detained by Abd el-Krim. One might add that even if the great powers still had a contentious relationship after the First World War, inter-imperial solidarity demanded that one did not encourage indigenous rebellions in case the example took.80

Although the war did not go unnoticed by the ICRC, the latter remained largely on the sidelines. It was not an international armed conflict, and therefore the applicable protection regime was ambiguous – if not absent –and there was no legal or formal basis for the ICRC to take action. This attitude was slightly inconsistent with the resolution and political courage that the ICRC had shown in the past, such as during the Anglo-Boer war (1899–1902), where the ICRC encouraged the Transvaal and the Free State of Orange81 to establish a Red Cross society and to accede to the Geneva Convention despite the strong objection of the British Crown, which contested the sovereignty of these entities. The ICRC and the Movement components had also taken humanitarian action in the Finland Civil War (1918), in Upper Silesia during the Russian Civil War (1919), the Ukraine War of Independence (1918–1921) and in Hungary during Béla Kun's communist uprising (1919), which were not inter-State conflicts.82 In all these situations, the ICRC quietly intervened without much resistance from legitimate or de facto authorities.

It was not until 1924, three years after the conflict began, that the ICRC started to become a little concerned with the situation in the Rif. This concern was mainly triggered by the mobilization of what would today be called civil society. According to the available sources,83 it is only after it was approached by charitable organizations and some national Red Cross societies already working in the region, alerting it of the severity of the situation and particularly that of refugees, that the ICRC took some action. In the end, it decided to send a representative to the Marquis of Hoyos, president of the Spanish Red Cross, who immediately retorted that “it was not a conflict, the needs of civilians were amply covered and so there was no justification for the ICRC to take action in the region”.84 The ICRC was only able to establish direct contact with the Spanish government once, through the Spanish Red Cross, but the reaction was similar. After being approached by the Near and Middle-East Association, a charitable organization concerned about the humanitarian situation in the Rif, ICRC Vice-President Paul des Gouttes confirmed that the ICRC could only take action on the express invitation of a warring party, and that Abd el-Krim did not have that status.

In the course of discussions and exchanges with Spanish authorities and the national Red Cross, further arguments were consistently claimed to obstruct any international intervention.85 These arguments would strangely resonate today for humanitarian negotiators attempting to gain a licence to operate in some modern conflicts:

Given the growing concern in the West, in November–December 1925 the ICRC nevertheless sent an envoy to the Tangier International Zone and to Rabat88 to enquire about the humanitarian situation and in particular about the fate of approximately 5000 Riffian refugees. However, no concrete action was taken at that stage. ICRC's missus dominicus, Dr Mentha, was unable to establish any contact with high-ranking officials or with the rebellion representatives or even with the Berber community as such. The whole affair left the impression of a lack of determination and tokenism.

The following year, the ICRC received from the Swedish Red Cross89 a copy of a letter sent by Abd el-Krim to the King of Sweden,90 informing him of civilian suffering, and it again sent a delegate to Rabat. On 23 May 1926, Abd el-Krim had already informed the French of his intention to surrender and so the ICRC's relief efforts were deemed to be unnecessary.91

It is surprising to see how fainthearted the ICRC was in the Rif affair given that, almost simultaneously, in 1925, it had taken very proactive steps in relation to the Druze revolt in Lebanon, then under French mandate. It showed a much more energetic approach to diplomacy by putting a delegate on the ship carrying France's new high commissioner to Beirut in order to negotiate ICRC action in Lebanon, a French protectorate.

There is no final explanation as to why the ICRC was so passive regarding the Rif War, but we can imagine that it was not inclined to alienate two European countries for the sake of an “indigenous revolt” that, at the time, did not appear comparable to conflicts between “civilized powers”. We may also suppose that the ICRC was more prone to consolidate and further develop the existing interstate conflict regulation than to spend political assets/resources on a colonial police operation. The French and Spanish Red Cross societies did consider their role as supporting their own troops and helping specific categories of victims but certainly not to offer impartial help to all people affected. Let us note that the issue of impartiality and independence of National Societies is still very prominent in many contexts where they have to operate in internal conflicts.

Before 1924, ICRC archives are mute on the Rif issue. We could not find any reference to the conflict; it is thus hazardous to deduce the level of information the Committee had before this date, or the content of discussions on this issue, if any. It is, however, established that the news from the Rif front had reached newspapers in Europe at least since the Battle of Annual (1921). It is highly improbable that committee members or the small administrative nucleus would have completely overlooked the unfolding events in Morocco92 before 1924.

However, it is difficult to interpret the ICRC's strategy and intentions merely based on available institutional archives. There are only assumptions about the ICRC's apparent unwillingness to act. Some authors93 argue that the ICRC was kept busy by other contexts where it was running assistance and repatriation programmes and most probably considered the situation in Morocco as being marginal. It is true that for the Committee the rules of war had been established to regulate warfare between “civilized nations”; however, despite the legal vacuum, it had serious concerns concerning the fate of civilians in conflict situations following atrocities committed by various armies during the First World War and its aftermath. In 1921, an ICRC delegate, Maurice Gehri, had, for example, published an account in the Review about the atrocities committed by the Greek army against the Muslim population in Anatolia.94 In that sense, it would be excessive to claim that the ICRC was totally blind to the suffering of non-European populations.

Until the end of 1924, it seems that the institution was very adamant not to upset the Spanish (more or less represented by the Spanish Red Cross), sometimes even responding to queries from other Red Cross societies by endorsing arguments put up by the Spanish authorities to justify their refusal of foreign aid. On the other hand, it would systematically forward to the Spanish Red Cross all letters and communications from National Societies and other charitable organizations voicing their concern about the situation prevailing in the Rif in a form that could be seen as a protracted and low-key advocacy manoeuvre. By 1925, the tone had changed, and the ICRC started to affirm its resolution to send an official or unofficial (unauthorized) mission to the Rif region.

In November 1925, the ICRC published in the Bulletin95 a rather extensive but clinical summary of decisions taken by it. This article brought clarification to why the organization had decided not to act, identifying itself with the arguments expressed by the Spanish Red Cross.

What must be underlined is that, in 1920, colonialism was not an undisputed policy and its legitimacy was already the subject of heated debates within European States. However, the international climate around the ICRC was still relatively conservative and responding to the plea of unruly natives looked like a potentially dangerous venture. The famous Wilson's fourteen-point programme in which self-determination was exposed was not addressing colonized people but countries like Poland or Czechoslovakia. The United States were largely retaining the idea that the role of colonial powers was to help “less civilized peoples achieve the habit of law and obedience”.96

In addition, the First World War had shown to the colonized people that “their masters” were not invincible. Colonial rulers were persuaded they had to retain their respective possessions in firm hands in order to avoid a disintegration of their respective empires.

In 1923, the informal embassy of the Rif government based in London sent a “Declaration of State and Proclamation to all Nations” to the LN reaffirming its independence and its desire to fight for its political recognition.97 In political terms, the LN had from the outset declared that it had no power to intervene, because the Treaty of Versailles had confirmed the major powers’ role as protectors of Morocco. The accounts from the period show that ICRC governance shared more or less that vision.98 The LN and the ICRC also agreed that Riffian fighters did not qualify as a “belligerent”. As a result, the LN refused to act as a mediator because it did not regard the Rif Republic as a national entity.99 It is interesting to note that, almost at the same time, France's military response to the Druze revolt in Lebanon, which spread to much of Syria, did not encounter the same lack of reaction from the LN because Syria was not a colony but a mandated territory. France would have to answer for its actions before the Permanent Mandates Commission and reassure the international community about the use of poison gas. The LN, when considering whether the Geneva Protocol on poison gases applied to Morocco, confirmed that it could only apply to belligerent States,100 which Spain and France were not, and the Riffians even less so. French perception, for example, was that the use of poison gas in the Rif context was an optional strategic possibility rather than the subject of total ban.

The difference in the ICRC's approach to the Rif War and its humanitarian efforts in the Second Italo–Ethiopian War ten years later is also striking, although it must be said that the latter was an international armed conflict taking place against a completely different political backdrop. It is also worth mentioning that in 1925 the ICRC was still a tiny organization that had almost no operational and financial capabilities. It was not until the Second Italo–Ethiopian War and the Spanish Civil War that the term “delegation” could be used to describe the ICRC's presence.101

For the ICRC, any humanitarian action without Madrid's consent would have been regarded as meddling in Spain's domestic affairs. The ICRC's Archives strongly indicate that ICRC management and governance at the time were more inclined to give credit to official State representatives involved than to the version of events that was in line with communications from charitable organizations, which were treated with great wariness. After its disappointing experience with the Spanish Red Cross, the ICRC directly approached the French government through the LN, but faced a similar refusal. A few months later, ICRC Vice-President Boissier102 added that he doubted in any case that Abd el-Krim would accept aid from an organization belonging to the “infidel” side. At no time did the ICRC make serious efforts to contact the rebel leader or his envoys.

We may conclude that the ICRC's “procrastination”, so to speak, may have had two distinct but intertwined causes. Firstly, there was a willingness to preserve and further develop what had been already achieved with existing States, and, more importantly, to get further legal codification.103 In 1920–1921, the ICRC was also very busy preserving its lead role within the Movement which was somewhat contested by the newly established League of the Red Cross. It seems that the ICRC wanted to protect its right of initiative (later recognized in 1928) and that Rif events did not fit in this strategy. Secondly, the lack of resources and operational experience to set up a large-scale humanitarian action in a non-European context was clearly a source of concern that transpired from the correspondence.

The Rif War stirred little reaction in Spain because the public still very strongly believed that every effort should be made to combat and punish “backward” peoples taking up arms against “civilizing forces”. Additionally, the various prisoner massacres and mutilation of dead bodies that took place in the 1920s’ offensive did not make the Riffian rebellion very popular. The mindset was very different from that which led to the Tragic Week in Barcelona in 1909, during which protests about soldiers being sent to Morocco turned into several days of extremely violent rioting in the city.

In France, a left-wing social-democrat coalition came to power in May 1924 and in 1925 it signed an agreement with Spain104 regarding joint military action in Morocco. What was most worrying to the French was the idea that, after the bloodbath that was the First World War, more young people – whose fathers had died in Verdun – would be sacrificed. The fate of the local people, meanwhile, was of no real concern. For France's Right and Far Right, the country needed to show that it was capable of defending itself and, above all, maintaining its place in the world. Only the French Communist Party (PCF) – initially accused by the Komintern of being ambiguous about colonial matters and supported by intellectuals including the Surrealist “Clarté” group – organized mass protests against the war, and particularly against the sending of troops to Morocco. At the end of 1924, the PCF also wrote “a pro Rif manifesto” and sent a telegram of support to Abd el-Krim105 that would be read before the National Assembly.

From 1925 to 1926 the controversy grew in Scandinavia. The publication of a series of articles reported very disturbing testimonies on the conduct of hostilities and the situation of the civilian population. Some authors did not hesitate to qualify military acts as crimes against humanity.106 Personalities like the explorer Sven Hedin107 used their prestige to serve the Riffian cause, to the chagrin of French diplomats, who multiplied efforts to discredit the information in these articles to the ICRC. They did their utmost to persuade public opinion that these personalities were serving foreign powers. Generally speaking, the joint military operation between France and Spain was the object of robust public diplomacy to avoid the emergence of international solidarity between Riffian nationalist forces and communist or anti-colonial movements.

Despite some gains in popular support, Abd el-Krim's efforts to garner foreign political support were largely unsuccessful. The UK government showed very vague sympathy, but offered no diplomatic help. In 1922, debates in the British Parliament showed very clearly that His Majesty's Government was not ready to intervene in any way in the affairs of “friendly Spain”.108

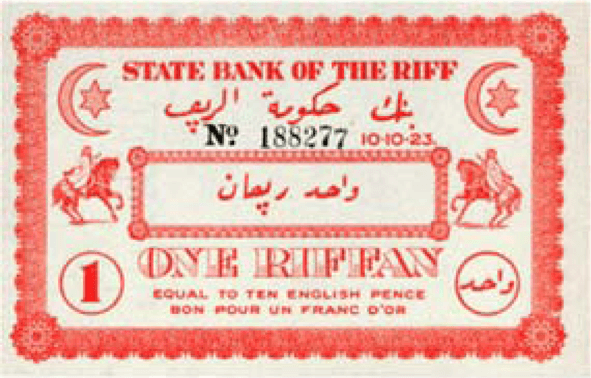

Abd el-Krim also struggled to convince other countries that the Rif Republic was a fledgling State, despite having very embryonic institutions (for example, a State Bank; see Figure 8). Robert Gordon Canning,109 chairman of the Rif Committee based in London, tried to intercede with France's Minister of Foreign Affairs Aristide Briand, but in vain. He put that refusal down to France being unable or unwilling to recognize the Rif authorities.

Figure 8. Bank note: State Bank of the Riff – Foreign Issues (1923) (Numizon).

For decades, the Rif War and its ephemeral Republic were not the object of significant political debate, and it only raised modest interest in academic circles.

However, in December 2018, Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs Josep Borrel declared that Spain would start a process of healing wounds on both sides, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Rif War.110 That stance followed a request, made by the Republican Left of Catalonia party, for Morocco to receive compensation for the use of chemical weapons. This was the first time that any reconciliation and reparation process had been openly mentioned. Mr Borrel announced that the process should also take into account the suffering caused by the Battle of Annual and of the 10,000 Spanish soldiers who died in it. The government had – in February 2018 – received a request from the Amazigh World Assembly (AMA),111 asking Spain to present its apologies for the use of chemical weapons in Morocco and proposing a compensation plan, but things did not advance further. The AMA also mentioned, in its request, the need to put in place a transitional justice mechanism.

Almost at the same time, Netflix broadcasted a series entitled Morocco: Love in Times of War (Tiempos de guerra),112 telling the story of Spanish Red Cross nurses in a military hospital in Melilla in 1921.

This slight resurgence of interest only partially masks the relative parsimony of historical studies on the Rif War, which is compounded with the almost total lack of collective memory about this period. This is not even a situation of competing memories in which diverging narratives collide and feed modern political controversies.

Whereas the Rif War was centre-stage politically in the late 1920s and was highly controversial in Europe between pro-colonial and anti-colonial forces, it did not elicit much scientific literature until very recently. However, it is one of the first examples of Western powers forming a coalition to wage a long and ruthless counter-insurgency campaign. It is also an example of the kind of asymmetric wars we are witnessing today. Although a major conflict, it has not been greatly explored by historians and represents a real black hole in terms of remembrance. It should be stressed that it was not just another police expedition aimed at subduing some restive natives using specialist colonial troops, or intended to make a local despot yield using a skillfully deployed gunboat. Rather, it was a large-scale conflict pursued using the most modern military resources of its time, and the excessive scale of those resources is still shocking today. It is likely that only the crackdown that followed the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (the Great Mutiny)113 or, more recently, the massacres of the Herero and Namas populations in Namibia114 (1904–1907) by the German Empire surpassed the Rif War in terms of civilian casualties.

Not surprisingly, there are very few monuments, commemorative works or gravestones specifically dedicated to the fighters killed during this campaign, not to mention the civilian casualties. A few names are mentioned in some military sections of national cemeteries in France and Spain, but that is about all. The victims of the conflict have faded from history. This situation is paradoxical if one considers the number of monuments to the dead that studded France after the First World War. Closer to us, the French government was until recently very reluctant to create remembrance places for its military personnel fallen in the so-called external operations.115

French philosopher Paul Ricœur116 explored what he called “les ruses de l'oubli” (tactical forgetting), which includes the removal of historical records, which may be conscious or unconscious but is in all cases collective. Among the French and Spanish, there has not yet been any political will to revisit an embarrassing colonial episode, which could also result in claims or requests for compensation that would be very complicated to address. France still struggles to approach the Algerian War with equanimity and Spain has not finished managing the heritage of the Franco regime and the Civil War.117 There are still numerous subjects of disagreement between Spain and Morocco, in particular the fate of the two Ceuta and Melilla enclaves, among others.

In 2007, Moroccan documentarian Tarik el-Adrissi made a film118 about the use of poison gas, which had relatively little impact in Morocco and Spain. The Rif War has been erased from collective consciousness, and is very rarely alluded to, even for ideological purposes. Objectively speaking, no protagonist, except maybe the fragmented Riffian community, has any interest in exhuming this historical episode. The “rediscovery” of a forgotten conflict necessarily stems from a political decision. In that regard, one could say that the current amnesia is the result of a deliberate political strategy, but there is not even clear evidence for that. Neither is it a case of the traditional conflict between official history and collective memory, as seen in debates about the Algerian War119 and Vichy France, for example. There are no eyewitnesses left who can tell us about what happened in the Rif. The historical imprint left by a war, which goes beyond the real-life experiences of the protagonists, varies from conflict to conflict but it remains entirely real. It is impossible to understand war in the Balkans during the Second World War without the Jasenovac concentration camp120 or the Ukraine without the Kuban famine or the Babi Yar massacres. In the case of the Rif, there is no collective remembrance of particular episodes that would strike the imagination, as even the Annual disaster is long forgotten.

Rebuilding a nation often involves inventing a national narrative or reconstructing its backstory retrospectively to ensure social cohesion. We may wonder if the Rif War and its humanitarian consequences warrant a more thorough scrutiny.

For a quarter of a century, lawyers, politicians, psychologists and historians have debated the role of collective memory in the socio-political sustainable resolution of conflicts (the Rwandan genocide, apartheid, the Bosnian War, the repressive regimes in Chile and Argentina, etc.). Pierre Nora121 clearly distinguishes the need for remembrance and the historical imperative and is wary of both. Henry Rousso122 warns against the excesses committed in the name of remembrance and the mental manipulation that can result. Conflicts do not end when the last shot is fired. Certain humanitarian issues, such as people who are missing and unaccounted for, eat away at societies for several decades after hostilities have ended.123 We know that acknowledging human suffering in conflict is often a preliminary step towards more ambitious phases of the social and political reconciliation and normalization processes. Unfortunately, this collective memory124 can be revived or manipulated by those who are not solely concerned with giving a voice to victims.

Some experts believe that forgetting is sometimes a great healer, meaning that reviving forgotten suffering is much riskier than letting injustices go unpunished.125 Others take the opposite view,126 claiming that there can be no reconciliation without some sort of recognition of the past, or without justice being served. As Australian aboriginal history and the Rwandan genocide have shown, denying and negating traumatic events seriously damage efforts to promote reconciliation or normalization, develop a peaceful society and establish lasting peace. The Kantian ideal of justice should win out over any other form of moral claim but the Battle of Annual happened four generations ago and its protagonists are long deceased. Nonetheless, it would be too hasty to ignore the symbolic weight127 of such events.128 The challenge in the case of the Rif War is that there is no one left to reconcile, which raises the following question: Can justice be served posthumously? A mechanism of restorative justice or compensation could doubtless be put in place but that would probably serve some political purpose being implemented.

The history of humanitarianism is still an emerging discipline, but it has seen significant growth in recent years and can only continue to do so. It is nonetheless difficult to examine conflicts before the 1960s, in particular colonial history, with a few rare exceptions.129

The rise of nationalist governments and community lobbies contributes to the risk of history being transformed in the name of the sacrosanct collective memory or duty to remember. These ideas can quickly serve to impose a national fiction, in some cases inscribed in law. We know that these “excesses in the duty of remembrance”,130 “competing victimhood” or the judicialization of historical “truths” are seriously detrimental to critical analysis and the comprehension of both facts and the intent of actors.131 History does not belong to historians alone132 and historians are not meant to produce adequate memorial discourse on command. However, humanitarian historians who study these questions must increasingly live with the fact that the discipline is not exclusively neutral and impartial, as the morality of the sector for which it is named. They must speak honestly about the defaults of collective memory with all unpleasant political consequences that this implies.

This article does not aim to determine whether remembrance is socially or politically necessary, nor to assess whether any confessions or reparations are legitimate demands for the Rif War. However, and without overstating the educational value of historical analysis, humanitarian historians should perhaps examine the Rif War more closely, over and above the remembrance efforts that are solely a matter for the people concerned. People make many strategic mistakes when they are unaware of history and when the subjective experience of those affected is rejected or misunderstood. Beyond its academic support, humanitarian history can also help clarify complex reconciliation processes, such as seen through the massacres in Namibia (1904–1907).

The Rif War is not yet really part of humanitarian history. The Boissier–Durand history of the ICRC between 1914 and 1945 which gives an account of the actions and initiatives of the Committee to send a mission to Morocco133 stands as the exception. Otherwise, it is curious to note that François Bugnion, in his magnum opus The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Protection of War Victims134 makes only a very short notice of a conflict which lasted for more than five years and caused tens of thousands of deaths. Michel Veuthey, in his seminal thesis on guerrilla warfare and humanitarian law,135 only mentions it briefly and in relation to the use of poison gas.

What is noteworthy about the Rif War is that, in its second phase, it involved a coalition of forces operating outside of their respective national territories, including regular armies, local back-up troops, tribes, mercenaries and even converted pirates. One can also discover the foundations of a sort of transnational mobilization of civil society.136 In this respect, it was a thoroughly modern conflict.

The Rif War was a rehearsal, taking place behind closed doors, for future colonial wars, but also to some extent for today's counter-insurgency and insurrection wars. It contained all the ingredients for widespread abuses and excesses. It raised all the issues and complexities relating to the protection of civilians during an internal armed conflict, and showed that States can be reluctant to allow organizations to do their work impartially. So, while the ICRC sent its General Delegate Raymond Schlemmer to Madrid in 1924 to meet Baron de Hoyos (President of the Spanish Red Cross) and the head of the political cabinet of Prime Minister Primo de Rivera, the arguments raised at that time against the ICRC's intervention strangely resound with the reasons put forward by some current governments to deny humanitarian presence or action. As for the “recognition of belligerency” in internal armed conflict, although the legal framework and customary law have considerably evolved since, it is still a recurrent problem when negotiating protection and humanitarian access.

It is striking to see that the powers involved in this conflict already considered that humanitarian action by external actors constituted a risk of political interference and possible politicization of any publicity that could be given to it.137 On top of this, aid could needlessly prolong the conflict, the presence of a foreign organization on rebel-held territory could in fact give a status to belligerents and the very nature of Riffian combatants, who did not understand the notion of humanity, did not allow the ICRC to act safely.138 Together, the Spanish government and Red Cross affirmed that the rebels were unwilling to be administered Western medicine and that, in any case, there were no longer civilians in the areas concerned. It is frustrating to see that the arguments used nowadays to deny the ICRC access in certain situations are exactly the same as those advanced 100 years ago.

Is the Rif War a mere historical episode to be filed alongside others such as the Crimean War, the Napoleonic campaigns or the Peloponnesian War? It is not as simple as that.

The humanitarian approach to history is valid because it relates to ideas and values that are still prompting discussion and controversy today. As such, the Battle of Solferino is of limited historical interest and was nothing like modern conflicts. The only reason it is important today, and has been since 1857, is because it gave rise to a conceptual revolution in the art of war and because it is the foundational moment of modern humanitarianism.

It would be tempting to state that nothing has really changed and that modern wars resemble old ones. However, wars have come a long way since 1920. Although the conflicts in Syria and Yemen might raise doubts about the usefulness and relevance of the law and of the international security system, few contemporary conflicts take place behind closed doors or in a legal vacuum that fosters impunity. The development of rules applicable to internal armed conflicts, although far from being perfect and fully implemented, has established a protection framework that can always be invoked and that has curbed the most serious excesses. States are now accountable for their actions. No regular army can ignore the law and carry out systematic, large-scale violations of the rules without risking international opprobrium. Humanitarian organizations now have a major presence on the ground, although working conditions are increasingly dangerous and access can be often uncertain.

In 1925, no European State disputed the idea that the colonial powers were entitled to settle their differences with native populations as they saw fit, without any sort of international scrutiny or constraints. The Rif was a colonial problem that needed to be settled as one might resolve a domestic dispute, behind closed doors using discretionary powers.

Since 1925, conflict regulations and the protection framework have considerably evolved, but the existing legal construction is repeatedly put into question. The current return to a rigid form of sovereignty, which is opposed to or imposed upon humanitarian organizations, needs to be monitored because it will inevitably make some States feel entitled to use unlimited force to settle political problems. This is in line with the current trend of the rise of “exceptionalist” regimes who also seek to deny certain categories of fighters the protections they are entitled to and therefore the obligations envisaged by international humanitarian law. At 100 years after the first skirmishes of the Rif War and despite the extraordinary accomplishment in terms of normative developments, these questions are at the heart of humanitarian endeavour.

It is usually very dangerous to assess the past using current political, legal and moral concepts,139 but it is fair to say that the ICRC could have done better during the Rif episode despite adverse political conditions. It would be presumptuous to say that the ICRC completely failed in its mission, but its lack of political daring doubtless helped to legitimate the dominant discourse of the time, according to which all victims were not equal. It adopted a passive and conservative attitude, probably grounded in its desire to preserve State support to the emerging legal framework on international armed conflicts.

As Yuval Noah Harari once said, “history does not study the past but rather transformations”.140 Since 1920, the evolution of the ICRC's operational practices and humanitarian diplomacy is striking. Over the years, it has developed the ability to translate strictly humanitarian concerns into a political language that States can understand and has managed to extend its mandate to the point of being sometimes accused of “mission creep by rejectionist states”. Max Weber141 has described this dilemma well as two fundamentally differing and irreconcilably opposed maxims. An organization can either be oriented to an ethic of responsibility (Verantwortungsethik), meaning that it is accountable for the foreseeable consequences of its actions, or to an ethic of conviction (Gesinnungsethik), in which it is accountable only for applying existing policies.

Confronted by new forms of warfare or simply new man-made harmful phenomena, the ICRC has to decide between preserving the existing protection architecture or venturing into unchartered waters. Through its right of initiative, the ICRC's identity is intrinsically linked to its ability to highlight the plight of victims above all other political or legal considerations when the circumstances require it, beyond positive law. In 1925, during an audience with the Spanish Ambassador Quinonès de Léon,142 ICRC representative Raymond Schlemmer declared that humanitarian duty “was clearly contradicting the diplomatic duty”. In this author's view, the ICRC is never so relevant as when it puts the humanitarian imperative before the norm.